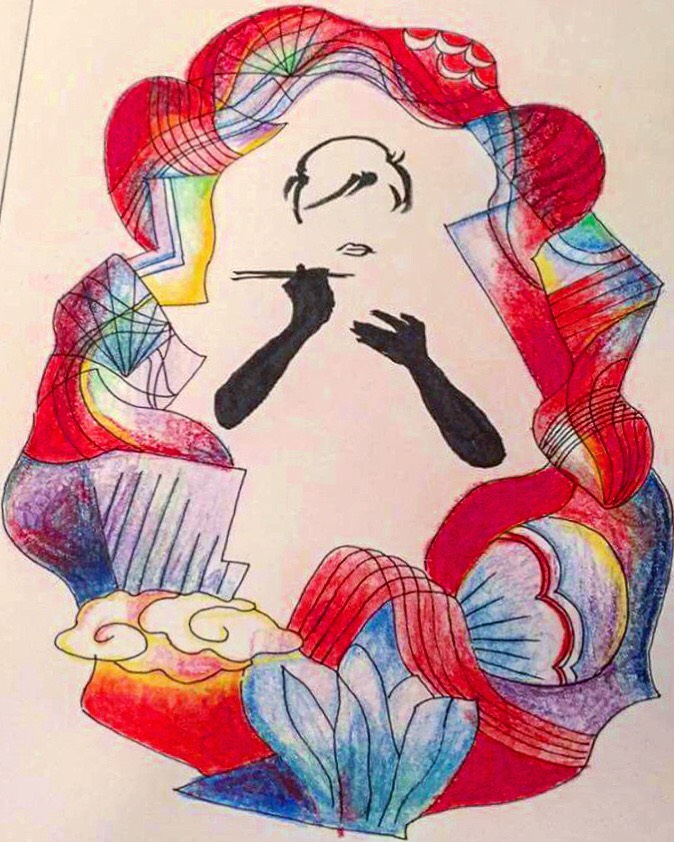

Image © Maari Sugawara 2018

| by Sheung-King | May 18, 2018 |

1

“There’s a bit of rice left on your plate.” You sip your wine.

We are having Thai food. It is a warm Sunday afternoon. I tell you a story – or rather, a series of events; I wonder what the difference is?

2

Once, there was a lord who loved to eat. He sometimes left his palace to find new flavours. One day, from far away, he smelled a smell like none other. He came to the house of a peasant woman. He begged to taste her food. She gave him some sugar cakes. He ate them all. He wanted more.

Peasant: That is all I have.

Lord: Come with me.

Where?

To my palace, where you will bake for me.

Why?

Because I like your cakes.

I will not come with you.

But I am a lord.

I will not come with you!

Then I will hit you.

The peasant had magical powers. She slapped the lord and the force threw him against the wall.

The lord was stuck to the wall.

The peasant woman placed a curse upon him.

He was to stay on the wall and watch other people eat, forever.

No one knew who the peasant woman was. No one had ever seen such a powerful curse. Not even the Jade Emperor could free the lord from the wall, so the Emperor appointed the lord Kitchen God. His altar was to be found near every family’s kitchen stove in China. Each year, he was to report to the Emperor of every family’s doings. The Jade Emperor would punish the families who had bad reports. Every New Year, families offered Kitchen God small, sticky, melon-shaped candies. His mouth became filled with sweetness. He could only report good things.

Some say the candies simply glued his mouth shut.

3

The Kitchen God also made sure that people didn’t waste food. My mother told me that. We had a domestic helper. My mother never cooked. Children who did not finish all of the rice in their bowls would be punished. Food left in children’s bowls would appear as warts on the faces of their future spouses.

I did not want my future spouse to grow warts. I only put a small amount of rice in my bowl.

When I was eleven, I discovered sushi. I liked sushi because I could finish a piece of sushi in one bite.

Would the Kitchen God be mad at me for eating Japanese food? Is the Kitchen God a Communist? Or did he only care about food? Nationalism, after the war, made its way into foods. “Rice in Japan is the most delicious rice in the world,” I once heard in a commercial. I agreed with that part of the commercial. Japanese rice was delicious. Japanese people must not have had warts on their faces. “Those who cook Japanese rice are the happiest,” continued the commercial. I am Chinese. I wondered what it meant for a Chinese person to eat Japanese rice.

When I turned twelve, I ate Japanese rice more often. Maybe I was swallowing Japanese nationalism. Maybe I was reinforcing it. What would the Kitchen God think?

I discovered that the Japanese character for rice, “米,” has the meaning “the root of life.” The Chinese character for rice is also “米,” which in Cantonese can mean wealth.

Rice is nationalism.

Rice is the root of life.

Rice is wealth.

4

“We were all thrown into the world at the start of our lives,” said Heidegger. Just as the lord was thrown against the wall, I was thrown into the world. The Kitchen God was stuck to the wall. I am stuck in the world.

I was thrown into Vancouver and moved to Hong Kong at the age of five. It was the early 2000s. I know of some Hong Kongers who were proud of having once been colonized by the British.

Why should I be so proud of where I live?

Some people were thrown into Hong Kong.

Some people were thrown into Vancouver.

The British ate mashed potatoes. I preferred sushi rice. I was never proud of living in a post-colonial city. I needed to prove that my life was separate from the nation, and from rice. I decided to throw away some uncooked rice. It was an act of resistance.

Uncooked rice is not in my bowl.

The Kitchen God cannot punish me.

My future spouse will not grow warts on her face.

5

Mother: What are you doing?

I am throwing away rice.

Why?

I explained to my mother that it was an act of resistance. We lived in an apartment on the 17th floor. I was throwing rice out the window. My mother struck me with a spatula.

My mother explained to me that throwing away rice was throwing away fortune.

I stopped my act of resistance. That night, my mother told the helper to not serve me any rice. Everyone else was served a bowl of hot steamed rice during dinner. The helper took away my chopsticks and gave me a spoon. Then she took away my bowl and gave me a plate. I had no choice but to have mashed potatoes for dinner. That was my punishment.

The Kitchen God was watching me.

I did not want my future spouse to grow warts because of me.

I stuffed the mashed potatoes in my mouth.

6

It is a beautiful Sunday afternoon. You finish your wine. You reach for your chopsticks. You are blushing a little. You pick up the rice that’s left on my plate. You eat the rice.

I touch your cheek.

Your face is perfectly smooth.

~End~

__________

Sheung-King (Aaron Tang) is a short story writer and playwright. His essays and stories can be found in Ricepaper Magazine, Currents: A Ricepaper Anthology, “The Liminal” by PRISM International, the Winter 2018 issue of the Humber Literary Review, as well as “Food for My People” by Exile Publishing. His play – Baguette is a finalist in the 2017 New Market National Play festival. Sheung-King is currently an MFA candidate in creative writing at the University of Guelph. He lives in Toronto.

Maari Sugawara holds a bachelor’s degree in Liberal Studies and a Curatorial Studies Diploma from Tokyo’s Waseda University. She also studied Art History at Queen’s University. She grew up in England and has curated art exhibitions in Tokyo, where she lives.